Interview

— Mr. Barsan, let me start by asking about your first acquaintance with Niko Pirosmani’s paintings. When did you find out about his life and art? Do you remember the first time you saw a Pirosmani’s work? What was your impression?

—Somewhere in Vienna, the city where every stone breathes with culture, I discovered an old bookshop. Inside, I let my eyes wander freely among forgotten books until a strange name drew my attention — Niko Pirosmani. This was in fall 2011.

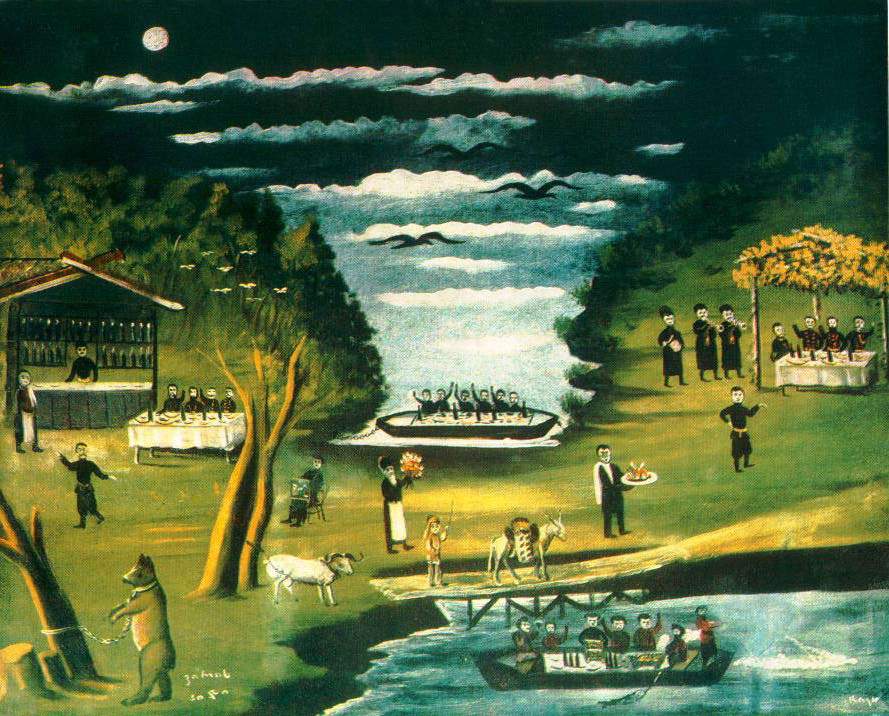

I was impressed by the complex simplicity and power of his paintings, their pure and free language that spoke straight to the heart. It was a strange feeling — a feeling of home, of the essence of things. Nothing more, nothing less.

— What strikes you in Pirosmani’s art? Could you name a painting or maybe a theme, a certain image that impresses you most?

— Pirosmani´s artistic language is what strikes me. His art is a clear, naked, vulnerable and free language formed by nature and instinct. He is a fast and spontaneous rendering. His art is fresh and youthful — it contains all things that mean youth!

His works accurately capture a certain harmony. Pirosmani succeeds in giving existence to works of art in the same way rain gives existence to flowers. And this kind of art needs nothing to be added to and nothing to be taken away from — it is complete just the way it is.

— You love Pirosmani’s art, but you are not a secret admirer, having done so much to popularize his name and his works. How and when the idea of Infinitart Foundation was born and how has it developed?

—To answer your question I must go back to 1989, to the event that was the ultimate cause of the foundation’s idea and development.

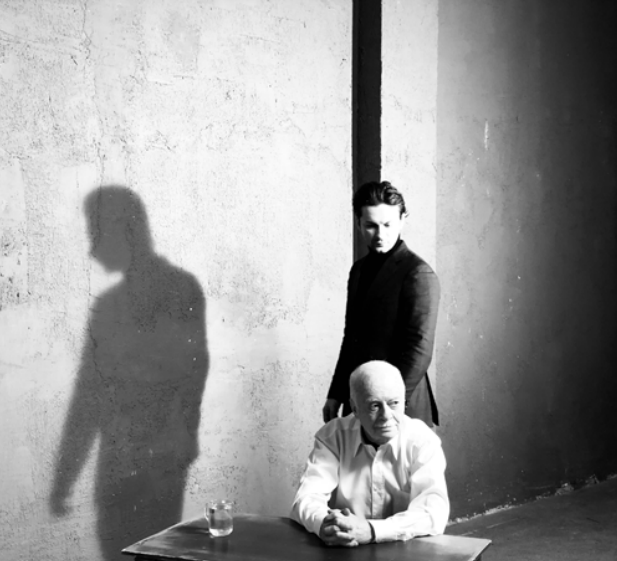

In 1989 my father’s hands were tied to the ceiling in a cold, wet solitary cell in Arad, Romania. My father’s blood was staining the sad, colorless ground as though red paint was coming from his wounds. That was the price he was paying under Ceaușescu’s regime for his desire for freedom — the freedom to choose the way of life and to express oneself.

In 1990 I grew up as a refugee child in Austria — a person without roots, without a native land and a native language. Very early in my childhood, I learned what it meant to be unable to speak the language that was accepted, understood and respected. It meant ridicule and exclusion.

The tragedy of existence unfolded in my heart. I did my best to escape, to endure, to forget that I was a foreigner without a nation. I was a lonely child. By accident, when I was about 14, I discovered the language of art and found solace in it — in the works of artists like Brâncuși or writers such as Emil Cioran, Octavian Paler — Romanians and others.

«It is no nation we inhabit, but a language. Make no mistake; our native tongue is our true homeland.» — Emil Cioran. «Next to the highest peak of happiness, there’s the deepest gap of pain.» — Octavian Paler.

Then I saw that art was indeed our mother tongue, our true homeland, because before there was a nation, before there was a word, there was the need for expression, and this expression came into existence in order to color the colorless loneliness. In Pirosmani, in his art, I have found a lonely artist who understands what life is about — with his art he overcomes and gives color to his colorless lonely life. For Pirosmani, art is liberation and freedom.

I have always wanted to share the solace found in art with the world, with people who feel hopeless and lonely, and to give them hope. I have been curious to see if art would have the same effect on them as I have experienced. That is the purpose of my foundation: to promote the one language that brings us all together — art.

Art is the manifestation of the spirit, and the spirit is infinite. No chains can hold the spirit.

—The exhibition at the Albertina was a success, and even those well familiar with Pirosmani’s art were impressed by the exhibition’s design and by the contemporary artworks which you’ve commissioned as a homage to Pirosmani. Was this your idea? How did you choose the artists? And these artists — Yoshitomo Nara, Kiki Smith, Adrian Ghenie — could you briefly describe the process of collaboration with them? Would it be correct to say that their works enter a dialogue with Pirosmani’s, offer their own perspective on his art?

— It was Pirosmani’s idea, not mine. I only brought it to life. The intention was to fulfill Pirosmani’s desire which he expressed in 1916 to the chairman of the newly founded Georgian Art Society, „…we ought to buy a big table and a big samovar and drink a lot of tea and talk about painting and art. But you don’t want this. You speak of other things.“

I wanted to bring artists through their works around Pirosmani´s Table — to celebrate his 100th anniversary as well as his rebirth in the awareness of hundreds of thousands who had never heard of Pirosmani or seen his art before.

And, speaking of this metaphorical rebirth, the idea was that Pirosmani be reborn surrounded with the living artists who would breathe life into the event.

I was looking for established artists who would be coming from a variety of cultural environments and nationalities and who’d each have found their own artistic language and style.

I was looking for artists who wouldn’t strive in the first place for a superficial, exterior harmony with Pirosmani´s art but bring an inner, organic connection — the free spirit — free language of self-expression, unprejudiced and open mind — I wanted to have diversity and to show that through the language of art we can create a bridge between the past to the present and on to the future, to connect different nations and different styles. The surface is not the essence. I spent hours with the artists and talked about Pirosmani.

Yes, their works enter a dialogue with Pirosmani. Every artist deals with him as a person and with his art. The homage works communicate directly with Pirosmani but remain true to their own artistic voice. Every artist should pay homage to him in their own language. I wanted to show that even accomplished artists from across the world recognize Pirosmani´s art as a source of inspiration.

— Tadao Ando’s Table is remarkable in many ways, as a beautiful work of art object and as an object around which people gather, sit and talk and understand each other. Could you share with us the story of its creation?

—The Pirosmani Table is a work of art with a deep metaphorical meaning. The idea of this artwork originates in the past — in the year 1916, to be precise — and it was expressed by Niko Pirosmani himself.

Pirosmani had remained destitute throughout his life; his works — only partly acknowledged as something more than mere posters — could not save him from poverty. With the full potential of his true talents remaining unrecognized during his lifetime, he was an outcast, even among his friends.

He died a lonely death in 1918 in a basement, and to this day it remains unknown where his body was buried. I have been deeply moved by his tragic fate and his words and promised to myself to create a memorial object for him. A memorial object in the form of a table; a tombstone for him as an artwork paying homage to his love for art. He lived through art and he died being in art. Art was freedom for him, and he died a free person.

The intention was to bring to reality Pirosmani’s idea, his forgotten dream, and in this way to transcend time and space, to connect the past, the present, and the future. To bring together different nationalities and languages, fulfilling Pirosmani’s wish.

So it’s a symbol around which friends can gather to celebrate life, beauty, love, and art; a table that he, Pirosmani, strove to erect during his lifetime.

For his art is above all an art of hospitality: an act of friendship, of welcome, of a shared celebration of simple joys and beauty of life, bringing together the artist and his audience in the same way a hearty and cordial Georgian meal brings together the host and the guests.

His sarcophagus, Pirosmani’s Table, pays homage to the painter’s idea: artists coming from different places have gathered around this table to talk about art. This table can bring together many people — just as Pirosmani wished — including artists, sculptors, architects, poets, educated people, uneducated people, scholars and working people; they will all be able to eat and drink, talk about art, sing, recite poems, and get to know each other, strangers becoming friends. Here is an invitation: come together and celebrate life in its fullest! Make a connection, a bridge that joins the past, the present, and the future — and the only future for humanity lies in unity. This artwork preserves the free spirit — the free language of self-expression and an unprejudiced, open mind.

Art is alive! Art always expresses some form of a mind phenomenon, a particular truth, or a state of mind. It was conceived as a dream of an artist from the past who was poor in life but rich in soul, a dream to build a table — to create a community. This artwork is a body, and the living contemporary artists will breathe life into it!

In 2018, 100 years after his death, the rebirth of Pirosmani’s dream came to reality, and the Table by Tadao Ando was presented in Vienna, the heart of Europe, at the Albertina Museum. To quote Tadao Ando: „As this table will represent the metaphorical tombstone of Niko Pirosmani, I sought to use a symbol which would give a respectful due to his memory, lifetime of work, and Georgian heritage.

The Rose is ephemeral, a fleeting representation of the short space between birth and death. The Rose is graceful, yet its thorns can pierce flesh, so it is a symbol of a contradiction between beauty and mortality.

Why blue roses, you may ask. Blue has a relaxing and soothing effect. It stands for peace, harmony, and fulfillment… With the color blue, we immediately associate the radiant sky and the wide sea. In literature, blue symbolizes the connection between human being and nature as well as our longing for the unattainable.

The color blue also plays an important role in art. The expressionist artists related to the Blaue Reiter group in the early 20th century paved the way for modern art. Pablo Picasso had a stage in his worked called the Blue Period, full of melancholy feelings, and Yves Klein often used in his art only this color.

The table is not a final result; it is a beginning, a symbol of unity and tolerance. All tongues deserve another’s ear and respect; strangers become siblings; there is no difference in value between woman and man, young and old, self-taught and schooled, between the elite and the less privileged… a wandering between worlds..

„There is neither […] slave nor free, there is no male nor female, for you are all one…“ [Galatians 3:28]

—On March 1, Pirosmani exhibition opened in Arles. Congratulations! Niko Pirosmani and Vincent van Gogh — what would you say these two geniuses have in common? It wasn’t by accident that you’ve chosen the Van Gogh Foundation Arles as the second venue for the Pirosmani exhibition. What are the main reasons?

Niko Pirosmani and Vincent van Gogh were born into two completely different cultural and geographical backgrounds. Nevertheless, the art of both painters has certain details that reveal a specific focus on the subject of humanity, which is especially relevant for the present-day art lovers.

Both self-taught artists communicate with the viewer in a very direct way, motivated by a sense of urgency. They create their works in clear connection with „common people,“ turning their artistic eye towards the archaic rural life, the human being who tills the earth in deep harmony with nature and the elements.

Their paintings are glowing images of iconic simplicity and of dreamlike, archetypal life. The style is energetic as the tempo does not permit pedantic lingering on details. The poignancy and forcefulness of the imagery are pushed to the limits. Graphical representation plays an eminent role in both artists’ work. While Pirosmani has a background as a sign painter, van Gogh is influenced by the highly stylized Japanese woodcuts. And most importantly, the Dutch painter is also a collector of those prints, an early form of mass-produced wall decoration made by illustrators who also worked for the newly emerging popular magazines.

Looking at Pirosmani brings into focus his audience as well: who were the people he was painting his pictures for? The popular discussion is dominated by the misleading idea of naive art produced in seclusion, even isolation. This is just as wrong as the assumption that Vincent van Gogh worked without relating to a possible audience. But whereas van Gogh imagined it would come in the near future for him and his „modern friends,“ along with the understanding of new ideas that would mature with time, Pirosmani had been in direct contact with his audience.

— The design of the exhibition in Arles again seems very impressive. How does the exhibition venue — the Van Gogh Foundation Arles — in fluence the concept? What is new in comparison with the exhibition at Albertina?

—At Albertina, we have celebrated Pirosmani’s 100th anniversary and his rebirth in the city of Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele who both died in 1918, like Pirosmani. The focus at Albertina was the idea of Pirosmani’s rebirth in the minds of many who had never heard of him before. The intention was to create a chapel, a shrine, a quiet and peaceful atmosphere. And we have achieved just that. The opening was the most successful in the history of the Albertina Museum, with more than 22,000 viewers following the opening ceremony online. Even our stop-motion exhibition promo clip turned out to be the most successful clip in Albertina´s history with more than 60,000 views, leaving behind even Egon Schiele’s, which reached around 50,000. And the exhibition itself was visited by more than 400,000 people.

To quote the Director of the Albertina Museum, Prof. Dr.Klaus Albrecht Schröder, „For me, the Niko Pirosmani exhibition stands among the most important exhibitions that Albertina has ever done.

In Arles, the place where van Gogh tried to preserve and express the light in his artistic language and where he created one of his greatest masterpieces, our objective was different: to create the opportunity to experience Pirosmani’s paintings in the colors of light. It is in this light, which blesses us with its joy, I intend to show Pirosmani. More specifically, visitors will see Pirosmani on differently colored walls. Pirosmani has never been displayed like that.

And I am very pleased with the exhibition and the curator’s work performed by my dear friend Ms. Bice Curiger, the Artistic Director of the Vincent van Gogh Foundation Arles. I would like to say that this may be the most beautiful Pirosmani exhibition in history. The different background colors of the walls that present Pirosmani’s work in different shades of light is something that has never been seen before.

— What are your plans? What will be the next stop for the exhibition?

—I would like to take the liberty of not revealing that at the moment but I’ll disclose what’s going to be the last stop of Pirosmani’s exhibition journey: The National Museum of Modern Art Tokyo and an encounter with Picasso

—Could you please tell us briefly about the publication´s plans, about the catalogue raisonne you’re preparing with Erast Kuznetsov, art historian and a leading Pirosmani expert…

— As for the catalogue, we are currently in talks with Cahiers D’Art Publishing House, which published the most well-known Pablo Picasso Catalogue Raisonne by Christian Zervos from 1932–1978.

— Mr. Barsan, let me start by asking about your first acquaintance with Niko Pirosmani’s paintings. When did you find out about his life and art? Do you remember the first time you saw a Pirosmani’s work? What was your impression?

—Somewhere in Vienna, the city where every stone breathes with culture, I discovered an old bookshop. Inside, I let my eyes wander freely among forgotten books until a strange name drew my attention — Niko Pirosmani. This was in fall 2011.

I was impressed by the complex simplicity and power of his paintings, their pure and free language that spoke straight to the heart. It was a strange feeling — a feeling of home, of the essence of things. Nothing more, nothing less.

— What strikes you in Pirosmani’s art? Could you name a painting or maybe a theme, a certain image that impresses you most?

— Pirosmani´s artistic language is what strikes me. His art is a clear, naked, vulnerable and free language formed by nature and instinct. He is a fast and spontaneous rendering. His art is fresh and youthful — it contains all things that mean youth!

His works accurately capture a certain harmony. Pirosmani succeeds in giving existence to works of art in the same way rain gives existence to flowers. And this kind of art needs nothing to be added to and nothing to be taken away from — it is complete just the way it is.

— You love Pirosmani’s art, but you are not a secret admirer, having done so much to popularize his name and his works. How and when the idea of Infinitart Foundation was born and how has it developed?

—To answer your question I must go back to 1989, to the event that was the ultimate cause of the foundation’s idea and development.

In 1989 my father’s hands were tied to the ceiling in a cold, wet solitary cell in Arad, Romania. My father’s blood was staining the sad, colorless ground as though red paint was coming from his wounds. That was the price he was paying under Ceaușescu’s regime for his desire for freedom — the freedom to choose the way of life and to express oneself.

In 1990 I grew up as a refugee child in Austria — a person without roots, without a native land and a native language. Very early in my childhood, I learned what it meant to be unable to speak the language that was accepted, understood and respected. It meant ridicule and exclusion.

The tragedy of existence unfolded in my heart. I did my best to escape, to endure, to forget that I was a foreigner without a nation. I was a lonely child. By accident, when I was about 14, I discovered the language of art and found solace in it — in the works of artists like Brâncuși or writers such as Emil Cioran, Octavian Paler — Romanians and others.

«It is no nation we inhabit, but a language. Make no mistake; our native tongue is our true homeland.» — Emil Cioran. «Next to the highest peak of happiness, there’s the deepest gap of pain.» — Octavian Paler.

Then I saw that art was indeed our mother tongue, our true homeland, because before there was a nation, before there was a word, there was the need for expression, and this expression came into existence in order to color the colorless loneliness. In Pirosmani, in his art, I have found a lonely artist who understands what life is about — with his art he overcomes and gives color to his colorless lonely life. For Pirosmani, art is liberation and freedom.

I have always wanted to share the solace found in art with the world, with people who feel hopeless and lonely, and to give them hope. I have been curious to see if art would have the same effect on them as I have experienced. That is the purpose of my foundation: to promote the one language that brings us all together — art.

Art is the manifestation of the spirit, and the spirit is infinite. No chains can hold the spirit.

—The exhibition at the Albertina was a success, and even those well familiar with Pirosmani’s art were impressed by the exhibition’s design and by the contemporary artworks which you’ve commissioned as a homage to Pirosmani. Was this your idea? How did you choose the artists? And these artists — Yoshitomo Nara, Kiki Smith, Adrian Ghenie — could you briefly describe the process of collaboration with them? Would it be correct to say that their works enter a dialogue with Pirosmani’s, offer their own perspective on his art?

— It was Pirosmani’s idea, not mine. I only brought it to life. The intention was to fulfill Pirosmani’s desire which he expressed in 1916 to the chairman of the newly founded Georgian Art Society, „…we ought to buy a big table and a big samovar and drink a lot of tea and talk about painting and art. But you don’t want this. You speak of other things.“

I wanted to bring artists through their works around Pirosmani´s Table — to celebrate his 100th anniversary as well as his rebirth in the awareness of hundreds of thousands who had never heard of Pirosmani or seen his art before.

And, speaking of this metaphorical rebirth, the idea was that Pirosmani be reborn surrounded with the living artists who would breathe life into the event.

I was looking for established artists who would be coming from a variety of cultural environments and nationalities and who’d each have found their own artistic language and style.

I was looking for artists who wouldn’t strive in the first place for a superficial, exterior harmony with Pirosmani´s art but bring an inner, organic connection — the free spirit — free language of self-expression, unprejudiced and open mind — I wanted to have diversity and to show that through the language of art we can create a bridge between the past to the present and on to the future, to connect different nations and different styles. The surface is not the essence. I spent hours with the artists and talked about Pirosmani.

Yes, their works enter a dialogue with Pirosmani. Every artist deals with him as a person and with his art. The homage works communicate directly with Pirosmani but remain true to their own artistic voice. Every artist should pay homage to him in their own language. I wanted to show that even accomplished artists from across the world recognize Pirosmani´s art as a source of inspiration.

— Tadao Ando’s Table is remarkable in many ways, as a beautiful work of art object and as an object around which people gather, sit and talk and understand each other. Could you share with us the story of its creation?

—The Pirosmani Table is a work of art with a deep metaphorical meaning. The idea of this artwork originates in the past — in the year 1916, to be precise — and it was expressed by Niko Pirosmani himself.

Pirosmani had remained destitute throughout his life; his works — only partly acknowledged as something more than mere posters — could not save him from poverty. With the full potential of his true talents remaining unrecognized during his lifetime, he was an outcast, even among his friends.

He died a lonely death in 1918 in a basement, and to this day it remains unknown where his body was buried. I have been deeply moved by his tragic fate and his words and promised to myself to create a memorial object for him. A memorial object in the form of a table; a tombstone for him as an artwork paying homage to his love for art. He lived through art and he died being in art. Art was freedom for him, and he died a free person.

The intention was to bring to reality Pirosmani’s idea, his forgotten dream, and in this way to transcend time and space, to connect the past, the present, and the future. To bring together different nationalities and languages, fulfilling Pirosmani’s wish.

So it’s a symbol around which friends can gather to celebrate life, beauty, love, and art; a table that he, Pirosmani, strove to erect during his lifetime.

For his art is above all an art of hospitality: an act of friendship, of welcome, of a shared celebration of simple joys and beauty of life, bringing together the artist and his audience in the same way a hearty and cordial Georgian meal brings together the host and the guests.

His sarcophagus, Pirosmani’s Table, pays homage to the painter’s idea: artists coming from different places have gathered around this table to talk about art. This table can bring together many people — just as Pirosmani wished — including artists, sculptors, architects, poets, educated people, uneducated people, scholars and working people; they will all be able to eat and drink, talk about art, sing, recite poems, and get to know each other, strangers becoming friends. Here is an invitation: come together and celebrate life in its fullest! Make a connection, a bridge that joins the past, the present, and the future — and the only future for humanity lies in unity. This artwork preserves the free spirit — the free language of self-expression and an unprejudiced, open mind.

Art is alive! Art always expresses some form of a mind phenomenon, a particular truth, or a state of mind. It was conceived as a dream of an artist from the past who was poor in life but rich in soul, a dream to build a table — to create a community. This artwork is a body, and the living contemporary artists will breathe life into it!

In 2018, 100 years after his death, the rebirth of Pirosmani’s dream came to reality, and the Table by Tadao Ando was presented in Vienna, the heart of Europe, at the Albertina Museum. To quote Tadao Ando: „As this table will represent the metaphorical tombstone of Niko Pirosmani, I sought to use a symbol which would give a respectful due to his memory, lifetime of work, and Georgian heritage.

The Rose is ephemeral, a fleeting representation of the short space between birth and death. The Rose is graceful, yet its thorns can pierce flesh, so it is a symbol of a contradiction between beauty and mortality.

Why blue roses, you may ask. Blue has a relaxing and soothing effect. It stands for peace, harmony, and fulfillment… With the color blue, we immediately associate the radiant sky and the wide sea. In literature, blue symbolizes the connection between human being and nature as well as our longing for the unattainable.

The color blue also plays an important role in art. The expressionist artists related to the Blaue Reiter group in the early 20th century paved the way for modern art. Pablo Picasso had a stage in his worked called the Blue Period, full of melancholy feelings, and Yves Klein often used in his art only this color.

The table is not a final result; it is a beginning, a symbol of unity and tolerance. All tongues deserve another’s ear and respect; strangers become siblings; there is no difference in value between woman and man, young and old, self-taught and schooled, between the elite and the less privileged… a wandering between worlds..

„There is neither […] slave nor free, there is no male nor female, for you are all one…“ [Galatians 3:28]

—On March 1, Pirosmani exhibition opened in Arles. Congratulations! Niko Pirosmani and Vincent van Gogh — what would you say these two geniuses have in common? It wasn’t by accident that you’ve chosen the Van Gogh Foundation Arles as the second venue for the Pirosmani exhibition. What are the main reasons?

Niko Pirosmani and Vincent van Gogh were born into two completely different cultural and geographical backgrounds. Nevertheless, the art of both painters has certain details that reveal a specific focus on the subject of humanity, which is especially relevant for the present-day art lovers.

Both self-taught artists communicate with the viewer in a very direct way, motivated by a sense of urgency. They create their works in clear connection with „common people,“ turning their artistic eye towards the archaic rural life, the human being who tills the earth in deep harmony with nature and the elements.

Their paintings are glowing images of iconic simplicity and of dreamlike, archetypal life. The style is energetic as the tempo does not permit pedantic lingering on details. The poignancy and forcefulness of the imagery are pushed to the limits. Graphical representation plays an eminent role in both artists’ work. While Pirosmani has a background as a sign painter, van Gogh is influenced by the highly stylized Japanese woodcuts. And most importantly, the Dutch painter is also a collector of those prints, an early form of mass-produced wall decoration made by illustrators who also worked for the newly emerging popular magazines.

Looking at Pirosmani brings into focus his audience as well: who were the people he was painting his pictures for? The popular discussion is dominated by the misleading idea of naive art produced in seclusion, even isolation. This is just as wrong as the assumption that Vincent van Gogh worked without relating to a possible audience. But whereas van Gogh imagined it would come in the near future for him and his „modern friends,“ along with the understanding of new ideas that would mature with time, Pirosmani had been in direct contact with his audience.

— The design of the exhibition in Arles again seems very impressive. How does the exhibition venue — the Van Gogh Foundation Arles — in fluence the concept? What is new in comparison with the exhibition at Albertina?

—At Albertina, we have celebrated Pirosmani’s 100th anniversary and his rebirth in the city of Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele who both died in 1918, like Pirosmani. The focus at Albertina was the idea of Pirosmani’s rebirth in the minds of many who had never heard of him before. The intention was to create a chapel, a shrine, a quiet and peaceful atmosphere. And we have achieved just that. The opening was the most successful in the history of the Albertina Museum, with more than 22,000 viewers following the opening ceremony online. Even our stop-motion exhibition promo clip turned out to be the most successful clip in Albertina´s history with more than 60,000 views, leaving behind even Egon Schiele’s, which reached around 50,000. And the exhibition itself was visited by more than 400,000 people.

To quote the Director of the Albertina Museum, Prof. Dr.Klaus Albrecht Schröder, „For me, the Niko Pirosmani exhibition stands among the most important exhibitions that Albertina has ever done.

In Arles, the place where van Gogh tried to preserve and express the light in his artistic language and where he created one of his greatest masterpieces, our objective was different: to create the opportunity to experience Pirosmani’s paintings in the colors of light. It is in this light, which blesses us with its joy, I intend to show Pirosmani. More specifically, visitors will see Pirosmani on differently colored walls. Pirosmani has never been displayed like that.

And I am very pleased with the exhibition and the curator’s work performed by my dear friend Ms. Bice Curiger, the Artistic Director of the Vincent van Gogh Foundation Arles. I would like to say that this may be the most beautiful Pirosmani exhibition in history. The different background colors of the walls that present Pirosmani’s work in different shades of light is something that has never been seen before.

— What are your plans? What will be the next stop for the exhibition?

—I would like to take the liberty of not revealing that at the moment but I’ll disclose what’s going to be the last stop of Pirosmani’s exhibition journey: The National Museum of Modern Art Tokyo and an encounter with Picasso

—Could you please tell us briefly about the publication´s plans, about the catalogue raisonne you’re preparing with Erast Kuznetsov, art historian and a leading Pirosmani expert…

— As for the catalogue, we are currently in talks with Cahiers D’Art Publishing House, which published the most well-known Pablo Picasso Catalogue Raisonne by Christian Zervos from 1932–1978.

— Mr. Barsan, let me start by asking about your first acquaintance with Niko Pirosmani’s paintings. When did you find out about his life and art? Do you remember the first time you saw a Pirosmani’s work? What was your impression?

—Somewhere in Vienna, the city where every stone breathes with culture, I discovered an old bookshop. Inside, I let my eyes wander freely among forgotten books until a strange name drew my attention — Niko Pirosmani. This was in fall 2011.

I was impressed by the complex simplicity and power of his paintings, their pure and free language that spoke straight to the heart. It was a strange feeling — a feeling of home, of the essence of things. Nothing more, nothing less.

— What strikes you in Pirosmani’s art? Could you name a painting or maybe a theme, a certain image that impresses you most?

— Pirosmani´s artistic language is what strikes me. His art is a clear, naked, vulnerable and free language formed by nature and instinct. He is a fast and spontaneous rendering. His art is fresh and youthful — it contains all things that mean youth!

His works accurately capture a certain harmony. Pirosmani succeeds in giving existence to works of art in the same way rain gives existence to flowers. And this kind of art needs nothing to be added to and nothing to be taken away from — it is complete just the way it is.

— You love Pirosmani’s art, but you are not a secret admirer, having done so much to popularize his name and his works. How and when the idea of Infinitart Foundation was born and how has it developed?

—To answer your question I must go back to 1989, to the event that was the ultimate cause of the foundation’s idea and development.

In 1989 my father’s hands were tied to the ceiling in a cold, wet solitary cell in Arad, Romania. My father’s blood was staining the sad, colorless ground as though red paint was coming from his wounds. That was the price he was paying under Ceaușescu’s regime for his desire for freedom — the freedom to choose the way of life and to express oneself.

In 1990 I grew up as a refugee child in Austria — a person without roots, without a native land and a native language. Very early in my childhood, I learned what it meant to be unable to speak the language that was accepted, understood and respected. It meant ridicule and exclusion.

The tragedy of existence unfolded in my heart. I did my best to escape, to endure, to forget that I was a foreigner without a nation. I was a lonely child. By accident, when I was about 14, I discovered the language of art and found solace in it — in the works of artists like Brâncuși or writers such as Emil Cioran, Octavian Paler — Romanians and others.

«It is no nation we inhabit, but a language. Make no mistake; our native tongue is our true homeland.» — Emil Cioran. «Next to the highest peak of happiness, there’s the deepest gap of pain.» — Octavian Paler.

Then I saw that art was indeed our mother tongue, our true homeland, because before there was a nation, before there was a word, there was the need for expression, and this expression came into existence in order to color the colorless loneliness. In Pirosmani, in his art, I have found a lonely artist who understands what life is about — with his art he overcomes and gives color to his colorless lonely life. For Pirosmani, art is liberation and freedom.

I have always wanted to share the solace found in art with the world, with people who feel hopeless and lonely, and to give them hope. I have been curious to see if art would have the same effect on them as I have experienced. That is the purpose of my foundation: to promote the one language that brings us all together — art.

Art is the manifestation of the spirit, and the spirit is infinite. No chains can hold the spirit.

—The exhibition at the Albertina was a success, and even those well familiar with Pirosmani’s art were impressed by the exhibition’s design and by the contemporary artworks which you’ve commissioned as a homage to Pirosmani. Was this your idea? How did you choose the artists? And these artists — Yoshitomo Nara, Kiki Smith, Adrian Ghenie — could you briefly describe the process of collaboration with them? Would it be correct to say that their works enter a dialogue with Pirosmani’s, offer their own perspective on his art?

— It was Pirosmani’s idea, not mine. I only brought it to life. The intention was to fulfill Pirosmani’s desire which he expressed in 1916 to the chairman of the newly founded Georgian Art Society, „…we ought to buy a big table and a big samovar and drink a lot of tea and talk about painting and art. But you don’t want this. You speak of other things.“

I wanted to bring artists through their works around Pirosmani´s Table — to celebrate his 100th anniversary as well as his rebirth in the awareness of hundreds of thousands who had never heard of Pirosmani or seen his art before.

And, speaking of this metaphorical rebirth, the idea was that Pirosmani be reborn surrounded with the living artists who would breathe life into the event.

I was looking for established artists who would be coming from a variety of cultural environments and nationalities and who’d each have found their own artistic language and style.

I was looking for artists who wouldn’t strive in the first place for a superficial, exterior harmony with Pirosmani´s art but bring an inner, organic connection — the free spirit — free language of self-expression, unprejudiced and open mind — I wanted to have diversity and to show that through the language of art we can create a bridge between the past to the present and on to the future, to connect different nations and different styles. The surface is not the essence. I spent hours with the artists and talked about Pirosmani.

Yes, their works enter a dialogue with Pirosmani. Every artist deals with him as a person and with his art. The homage works communicate directly with Pirosmani but remain true to their own artistic voice. Every artist should pay homage to him in their own language. I wanted to show that even accomplished artists from across the world recognize Pirosmani´s art as a source of inspiration.

— Tadao Ando’s Table is remarkable in many ways, as a beautiful work of art object and as an object around which people gather, sit and talk and understand each other. Could you share with us the story of its creation?

—The Pirosmani Table is a work of art with a deep metaphorical meaning. The idea of this artwork originates in the past — in the year 1916, to be precise — and it was expressed by Niko Pirosmani himself.

Pirosmani had remained destitute throughout his life; his works — only partly acknowledged as something more than mere posters — could not save him from poverty. With the full potential of his true talents remaining unrecognized during his lifetime, he was an outcast, even among his friends.

He died a lonely death in 1918 in a basement, and to this day it remains unknown where his body was buried. I have been deeply moved by his tragic fate and his words and promised to myself to create a memorial object for him. A memorial object in the form of a table; a tombstone for him as an artwork paying homage to his love for art. He lived through art and he died being in art. Art was freedom for him, and he died a free person.

The intention was to bring to reality Pirosmani’s idea, his forgotten dream, and in this way to transcend time and space, to connect the past, the present, and the future. To bring together different nationalities and languages, fulfilling Pirosmani’s wish.

So it’s a symbol around which friends can gather to celebrate life, beauty, love, and art; a table that he, Pirosmani, strove to erect during his lifetime.

For his art is above all an art of hospitality: an act of friendship, of welcome, of a shared celebration of simple joys and beauty of life, bringing together the artist and his audience in the same way a hearty and cordial Georgian meal brings together the host and the guests.

His sarcophagus, Pirosmani’s Table, pays homage to the painter’s idea: artists coming from different places have gathered around this table to talk about art. This table can bring together many people — just as Pirosmani wished — including artists, sculptors, architects, poets, educated people, uneducated people, scholars and working people; they will all be able to eat and drink, talk about art, sing, recite poems, and get to know each other, strangers becoming friends. Here is an invitation: come together and celebrate life in its fullest! Make a connection, a bridge that joins the past, the present, and the future — and the only future for humanity lies in unity. This artwork preserves the free spirit — the free language of self-expression and an unprejudiced, open mind.

Art is alive! Art always expresses some form of a mind phenomenon, a particular truth, or a state of mind. It was conceived as a dream of an artist from the past who was poor in life but rich in soul, a dream to build a table — to create a community. This artwork is a body, and the living contemporary artists will breathe life into it!

In 2018, 100 years after his death, the rebirth of Pirosmani’s dream came to reality, and the Table by Tadao Ando was presented in Vienna, the heart of Europe, at the Albertina Museum. To quote Tadao Ando: „As this table will represent the metaphorical tombstone of Niko Pirosmani, I sought to use a symbol which would give a respectful due to his memory, lifetime of work, and Georgian heritage.

The Rose is ephemeral, a fleeting representation of the short space between birth and death. The Rose is graceful, yet its thorns can pierce flesh, so it is a symbol of a contradiction between beauty and mortality.

Why blue roses, you may ask. Blue has a relaxing and soothing effect. It stands for peace, harmony, and fulfillment… With the color blue, we immediately associate the radiant sky and the wide sea. In literature, blue symbolizes the connection between human being and nature as well as our longing for the unattainable.

The color blue also plays an important role in art. The expressionist artists related to the Blaue Reiter group in the early 20th century paved the way for modern art. Pablo Picasso had a stage in his worked called the Blue Period, full of melancholy feelings, and Yves Klein often used in his art only this color.

The table is not a final result; it is a beginning, a symbol of unity and tolerance. All tongues deserve another’s ear and respect; strangers become siblings; there is no difference in value between woman and man, young and old, self-taught and schooled, between the elite and the less privileged… a wandering between worlds..

„There is neither […] slave nor free, there is no male nor female, for you are all one…“ [Galatians 3:28]

—On March 1, Pirosmani exhibition opened in Arles. Congratulations! Niko Pirosmani and Vincent van Gogh — what would you say these two geniuses have in common? It wasn’t by accident that you’ve chosen the Van Gogh Foundation Arles as the second venue for the Pirosmani exhibition. What are the main reasons?

Niko Pirosmani and Vincent van Gogh were born into two completely different cultural and geographical backgrounds. Nevertheless, the art of both painters has certain details that reveal a specific focus on the subject of humanity, which is especially relevant for the present-day art lovers.

Both self-taught artists communicate with the viewer in a very direct way, motivated by a sense of urgency. They create their works in clear connection with „common people,“ turning their artistic eye towards the archaic rural life, the human being who tills the earth in deep harmony with nature and the elements.

Their paintings are glowing images of iconic simplicity and of dreamlike, archetypal life. The style is energetic as the tempo does not permit pedantic lingering on details. The poignancy and forcefulness of the imagery are pushed to the limits. Graphical representation plays an eminent role in both artists’ work. While Pirosmani has a background as a sign painter, van Gogh is influenced by the highly stylized Japanese woodcuts. And most importantly, the Dutch painter is also a collector of those prints, an early form of mass-produced wall decoration made by illustrators who also worked for the newly emerging popular magazines.

Looking at Pirosmani brings into focus his audience as well: who were the people he was painting his pictures for? The popular discussion is dominated by the misleading idea of naive art produced in seclusion, even isolation. This is just as wrong as the assumption that Vincent van Gogh worked without relating to a possible audience. But whereas van Gogh imagined it would come in the near future for him and his „modern friends,“ along with the understanding of new ideas that would mature with time, Pirosmani had been in direct contact with his audience.

— The design of the exhibition in Arles again seems very impressive. How does the exhibition venue — the Van Gogh Foundation Arles — in fluence the concept? What is new in comparison with the exhibition at Albertina?

—At Albertina, we have celebrated Pirosmani’s 100th anniversary and his rebirth in the city of Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele who both died in 1918, like Pirosmani. The focus at Albertina was the idea of Pirosmani’s rebirth in the minds of many who had never heard of him before. The intention was to create a chapel, a shrine, a quiet and peaceful atmosphere. And we have achieved just that. The opening was the most successful in the history of the Albertina Museum, with more than 22,000 viewers following the opening ceremony online. Even our stop-motion exhibition promo clip turned out to be the most successful clip in Albertina´s history with more than 60,000 views, leaving behind even Egon Schiele’s, which reached around 50,000. And the exhibition itself was visited by more than 400,000 people.

To quote the Director of the Albertina Museum, Prof. Dr.Klaus Albrecht Schröder, „For me, the Niko Pirosmani exhibition stands among the most important exhibitions that Albertina has ever done.

In Arles, the place where van Gogh tried to preserve and express the light in his artistic language and where he created one of his greatest masterpieces, our objective was different: to create the opportunity to experience Pirosmani’s paintings in the colors of light. It is in this light, which blesses us with its joy, I intend to show Pirosmani. More specifically, visitors will see Pirosmani on differently colored walls. Pirosmani has never been displayed like that.

And I am very pleased with the exhibition and the curator’s work performed by my dear friend Ms. Bice Curiger, the Artistic Director of the Vincent van Gogh Foundation Arles. I would like to say that this may be the most beautiful Pirosmani exhibition in history. The different background colors of the walls that present Pirosmani’s work in different shades of light is something that has never been seen before.

— What are your plans? What will be the next stop for the exhibition?

—I would like to take the liberty of not revealing that at the moment but I’ll disclose what’s going to be the last stop of Pirosmani’s exhibition journey: The National Museum of Modern Art Tokyo and an encounter with Picasso

—Could you please tell us briefly about the publication´s plans, about the catalogue raisonne you’re preparing with Erast Kuznetsov, art historian and a leading Pirosmani expert…

— As for the catalogue, we are currently in talks with Cahiers D’Art Publishing House, which published the most well-known Pablo Picasso Catalogue Raisonne by Christian Zervos from 1932–1978.

— Mr. Barsan, let me start by asking about your first acquaintance with Niko Pirosmani’s paintings. When did you find out about his life and art? Do you remember the first time you saw a Pirosmani’s work? What was your impression?

—Somewhere in Vienna, the city where every stone breathes with culture, I discovered an old bookshop. Inside, I let my eyes wander freely among forgotten books until a strange name drew my attention — Niko Pirosmani. This was in fall 2011.

I was impressed by the complex simplicity and power of his paintings, their pure and free language that spoke straight to the heart. It was a strange feeling — a feeling of home, of the essence of things. Nothing more, nothing less.

— What strikes you in Pirosmani’s art? Could you name a painting or maybe a theme, a certain image that impresses you most?

— Pirosmani´s artistic language is what strikes me. His art is a clear, naked, vulnerable and free language formed by nature and instinct. He is a fast and spontaneous rendering. His art is fresh and youthful — it contains all things that mean youth!

His works accurately capture a certain harmony. Pirosmani succeeds in giving existence to works of art in the same way rain gives existence to flowers. And this kind of art needs nothing to be added to and nothing to be taken away from — it is complete just the way it is.

— You love Pirosmani’s art, but you are not a secret admirer, having done so much to popularize his name and his works. How and when the idea of Infinitart Foundation was born and how has it developed?

—To answer your question I must go back to 1989, to the event that was the ultimate cause of the foundation’s idea and development.

In 1989 my father’s hands were tied to the ceiling in a cold, wet solitary cell in Arad, Romania. My father’s blood was staining the sad, colorless ground as though red paint was coming from his wounds. That was the price he was paying under Ceaușescu’s regime for his desire for freedom — the freedom to choose the way of life and to express oneself.

In 1990 I grew up as a refugee child in Austria — a person without roots, without a native land and a native language. Very early in my childhood, I learned what it meant to be unable to speak the language that was accepted, understood and respected. It meant ridicule and exclusion.

The tragedy of existence unfolded in my heart. I did my best to escape, to endure, to forget that I was a foreigner without a nation. I was a lonely child. By accident, when I was about 14, I discovered the language of art and found solace in it — in the works of artists like Brâncuși or writers such as Emil Cioran, Octavian Paler — Romanians and others.

«It is no nation we inhabit, but a language. Make no mistake; our native tongue is our true homeland.» — Emil Cioran. «Next to the highest peak of happiness, there’s the deepest gap of pain.» — Octavian Paler.

Then I saw that art was indeed our mother tongue, our true homeland, because before there was a nation, before there was a word, there was the need for expression, and this expression came into existence in order to color the colorless loneliness. In Pirosmani, in his art, I have found a lonely artist who understands what life is about — with his art he overcomes and gives color to his colorless lonely life. For Pirosmani, art is liberation and freedom.

I have always wanted to share the solace found in art with the world, with people who feel hopeless and lonely, and to give them hope. I have been curious to see if art would have the same effect on them as I have experienced. That is the purpose of my foundation: to promote the one language that brings us all together — art.

Art is the manifestation of the spirit, and the spirit is infinite. No chains can hold the spirit.

—The exhibition at the Albertina was a success, and even those well familiar with Pirosmani’s art were impressed by the exhibition’s design and by the contemporary artworks which you’ve commissioned as a homage to Pirosmani. Was this your idea? How did you choose the artists? And these artists — Yoshitomo Nara, Kiki Smith, Adrian Ghenie — could you briefly describe the process of collaboration with them? Would it be correct to say that their works enter a dialogue with Pirosmani’s, offer their own perspective on his art?

— It was Pirosmani’s idea, not mine. I only brought it to life. The intention was to fulfill Pirosmani’s desire which he expressed in 1916 to the chairman of the newly founded Georgian Art Society, „…we ought to buy a big table and a big samovar and drink a lot of tea and talk about painting and art. But you don’t want this. You speak of other things.“

I wanted to bring artists through their works around Pirosmani´s Table — to celebrate his 100th anniversary as well as his rebirth in the awareness of hundreds of thousands who had never heard of Pirosmani or seen his art before.

And, speaking of this metaphorical rebirth, the idea was that Pirosmani be reborn surrounded with the living artists who would breathe life into the event.

I was looking for established artists who would be coming from a variety of cultural environments and nationalities and who’d each have found their own artistic language and style.

I was looking for artists who wouldn’t strive in the first place for a superficial, exterior harmony with Pirosmani´s art but bring an inner, organic connection — the free spirit — free language of self-expression, unprejudiced and open mind — I wanted to have diversity and to show that through the language of art we can create a bridge between the past to the present and on to the future, to connect different nations and different styles. The surface is not the essence. I spent hours with the artists and talked about Pirosmani.

Yes, their works enter a dialogue with Pirosmani. Every artist deals with him as a person and with his art. The homage works communicate directly with Pirosmani but remain true to their own artistic voice. Every artist should pay homage to him in their own language. I wanted to show that even accomplished artists from across the world recognize Pirosmani´s art as a source of inspiration.

— Tadao Ando’s Table is remarkable in many ways, as a beautiful work of art object and as an object around which people gather, sit and talk and understand each other. Could you share with us the story of its creation?

—The Pirosmani Table is a work of art with a deep metaphorical meaning. The idea of this artwork originates in the past — in the year 1916, to be precise — and it was expressed by Niko Pirosmani himself.

Pirosmani had remained destitute throughout his life; his works — only partly acknowledged as something more than mere posters — could not save him from poverty. With the full potential of his true talents remaining unrecognized during his lifetime, he was an outcast, even among his friends.

He died a lonely death in 1918 in a basement, and to this day it remains unknown where his body was buried. I have been deeply moved by his tragic fate and his words and promised to myself to create a memorial object for him. A memorial object in the form of a table; a tombstone for him as an artwork paying homage to his love for art. He lived through art and he died being in art. Art was freedom for him, and he died a free person.

The intention was to bring to reality Pirosmani’s idea, his forgotten dream, and in this way to transcend time and space, to connect the past, the present, and the future. To bring together different nationalities and languages, fulfilling Pirosmani’s wish.

So it’s a symbol around which friends can gather to celebrate life, beauty, love, and art; a table that he, Pirosmani, strove to erect during his lifetime.

For his art is above all an art of hospitality: an act of friendship, of welcome, of a shared celebration of simple joys and beauty of life, bringing together the artist and his audience in the same way a hearty and cordial Georgian meal brings together the host and the guests.

His sarcophagus, Pirosmani’s Table, pays homage to the painter’s idea: artists coming from different places have gathered around this table to talk about art. This table can bring together many people — just as Pirosmani wished — including artists, sculptors, architects, poets, educated people, uneducated people, scholars and working people; they will all be able to eat and drink, talk about art, sing, recite poems, and get to know each other, strangers becoming friends. Here is an invitation: come together and celebrate life in its fullest! Make a connection, a bridge that joins the past, the present, and the future — and the only future for humanity lies in unity. This artwork preserves the free spirit — the free language of self-expression and an unprejudiced, open mind.

Art is alive! Art always expresses some form of a mind phenomenon, a particular truth, or a state of mind. It was conceived as a dream of an artist from the past who was poor in life but rich in soul, a dream to build a table — to create a community. This artwork is a body, and the living contemporary artists will breathe life into it!

In 2018, 100 years after his death, the rebirth of Pirosmani’s dream came to reality, and the Table by Tadao Ando was presented in Vienna, the heart of Europe, at the Albertina Museum. To quote Tadao Ando: „As this table will represent the metaphorical tombstone of Niko Pirosmani, I sought to use a symbol which would give a respectful due to his memory, lifetime of work, and Georgian heritage.

The Rose is ephemeral, a fleeting representation of the short space between birth and death. The Rose is graceful, yet its thorns can pierce flesh, so it is a symbol of a contradiction between beauty and mortality.

Why blue roses, you may ask. Blue has a relaxing and soothing effect. It stands for peace, harmony, and fulfillment… With the color blue, we immediately associate the radiant sky and the wide sea. In literature, blue symbolizes the connection between human being and nature as well as our longing for the unattainable.

The color blue also plays an important role in art. The expressionist artists related to the Blaue Reiter group in the early 20th century paved the way for modern art. Pablo Picasso had a stage in his worked called the Blue Period, full of melancholy feelings, and Yves Klein often used in his art only this color.

The table is not a final result; it is a beginning, a symbol of unity and tolerance. All tongues deserve another’s ear and respect; strangers become siblings; there is no difference in value between woman and man, young and old, self-taught and schooled, between the elite and the less privileged… a wandering between worlds..

„There is neither […] slave nor free, there is no male nor female, for you are all one…“ [Galatians 3:28]

—On March 1, Pirosmani exhibition opened in Arles. Congratulations! Niko Pirosmani and Vincent van Gogh — what would you say these two geniuses have in common? It wasn’t by accident that you’ve chosen the Van Gogh Foundation Arles as the second venue for the Pirosmani exhibition. What are the main reasons?

Niko Pirosmani and Vincent van Gogh were born into two completely different cultural and geographical backgrounds. Nevertheless, the art of both painters has certain details that reveal a specific focus on the subject of humanity, which is especially relevant for the present-day art lovers.

Both self-taught artists communicate with the viewer in a very direct way, motivated by a sense of urgency. They create their works in clear connection with „common people,“ turning their artistic eye towards the archaic rural life, the human being who tills the earth in deep harmony with nature and the elements.

Their paintings are glowing images of iconic simplicity and of dreamlike, archetypal life. The style is energetic as the tempo does not permit pedantic lingering on details. The poignancy and forcefulness of the imagery are pushed to the limits. Graphical representation plays an eminent role in both artists’ work. While Pirosmani has a background as a sign painter, van Gogh is influenced by the highly stylized Japanese woodcuts. And most importantly, the Dutch painter is also a collector of those prints, an early form of mass-produced wall decoration made by illustrators who also worked for the newly emerging popular magazines.

Looking at Pirosmani brings into focus his audience as well: who were the people he was painting his pictures for? The popular discussion is dominated by the misleading idea of naive art produced in seclusion, even isolation. This is just as wrong as the assumption that Vincent van Gogh worked without relating to a possible audience. But whereas van Gogh imagined it would come in the near future for him and his „modern friends,“ along with the understanding of new ideas that would mature with time, Pirosmani had been in direct contact with his audience.

— The design of the exhibition in Arles again seems very impressive. How does the exhibition venue — the Van Gogh Foundation Arles — in fluence the concept? What is new in comparison with the exhibition at Albertina?

—At Albertina, we have celebrated Pirosmani’s 100th anniversary and his rebirth in the city of Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele who both died in 1918, like Pirosmani. The focus at Albertina was the idea of Pirosmani’s rebirth in the minds of many who had never heard of him before. The intention was to create a chapel, a shrine, a quiet and peaceful atmosphere. And we have achieved just that. The opening was the most successful in the history of the Albertina Museum, with more than 22,000 viewers following the opening ceremony online. Even our stop-motion exhibition promo clip turned out to be the most successful clip in Albertina´s history with more than 60,000 views, leaving behind even Egon Schiele’s, which reached around 50,000. And the exhibition itself was visited by more than 400,000 people.

To quote the Director of the Albertina Museum, Prof. Dr.Klaus Albrecht Schröder, „For me, the Niko Pirosmani exhibition stands among the most important exhibitions that Albertina has ever done.

In Arles, the place where van Gogh tried to preserve and express the light in his artistic language and where he created one of his greatest masterpieces, our objective was different: to create the opportunity to experience Pirosmani’s paintings in the colors of light. It is in this light, which blesses us with its joy, I intend to show Pirosmani. More specifically, visitors will see Pirosmani on differently colored walls. Pirosmani has never been displayed like that.

And I am very pleased with the exhibition and the curator’s work performed by my dear friend Ms. Bice Curiger, the Artistic Director of the Vincent van Gogh Foundation Arles. I would like to say that this may be the most beautiful Pirosmani exhibition in history. The different background colors of the walls that present Pirosmani’s work in different shades of light is something that has never been seen before.

— What are your plans? What will be the next stop for the exhibition?

—I would like to take the liberty of not revealing that at the moment but I’ll disclose what’s going to be the last stop of Pirosmani’s exhibition journey: The National Museum of Modern Art Tokyo and an encounter with Picasso

—Could you please tell us briefly about the publication´s plans, about the catalogue raisonne you’re preparing with Erast Kuznetsov, art historian and a leading Pirosmani expert…

— As for the catalogue, we are currently in talks with Cahiers D’Art Publishing House, which published the most well-known Pablo Picasso Catalogue Raisonne by Christian Zervos from 1932–1978.

— Mr. Barsan, let me start by asking about your first acquaintance with Niko Pirosmani’s paintings. When did you find out about his life and art? Do you remember the first time you saw a Pirosmani’s work? What was your impression?

—Somewhere in Vienna, the city where every stone breathes with culture, I discovered an old bookshop. Inside, I let my eyes wander freely among forgotten books until a strange name drew my attention — Niko Pirosmani. This was in fall 2011.

I was impressed by the complex simplicity and power of his paintings, their pure and free language that spoke straight to the heart. It was a strange feeling — a feeling of home, of the essence of things. Nothing more, nothing less.

— What strikes you in Pirosmani’s art? Could you name a painting or maybe a theme, a certain image that impresses you most?

— Pirosmani´s artistic language is what strikes me. His art is a clear, naked, vulnerable and free language formed by nature and instinct. He is a fast and spontaneous rendering. His art is fresh and youthful — it contains all things that mean youth!

His works accurately capture a certain harmony. Pirosmani succeeds in giving existence to works of art in the same way rain gives existence to flowers. And this kind of art needs nothing to be added to and nothing to be taken away from — it is complete just the way it is.

— You love Pirosmani’s art, but you are not a secret admirer, having done so much to popularize his name and his works. How and when the idea of Infinitart Foundation was born and how has it developed?

—To answer your question I must go back to 1989, to the event that was the ultimate cause of the foundation’s idea and development.

In 1989 my father’s hands were tied to the ceiling in a cold, wet solitary cell in Arad, Romania. My father’s blood was staining the sad, colorless ground as though red paint was coming from his wounds. That was the price he was paying under Ceaușescu’s regime for his desire for freedom — the freedom to choose the way of life and to express oneself.

In 1990 I grew up as a refugee child in Austria — a person without roots, without a native land and a native language. Very early in my childhood, I learned what it meant to be unable to speak the language that was accepted, understood and respected. It meant ridicule and exclusion.

The tragedy of existence unfolded in my heart. I did my best to escape, to endure, to forget that I was a foreigner without a nation. I was a lonely child. By accident, when I was about 14, I discovered the language of art and found solace in it — in the works of artists like Brâncuși or writers such as Emil Cioran, Octavian Paler — Romanians and others.

«It is no nation we inhabit, but a language. Make no mistake; our native tongue is our true homeland.» — Emil Cioran. «Next to the highest peak of happiness, there’s the deepest gap of pain.» — Octavian Paler.

Then I saw that art was indeed our mother tongue, our true homeland, because before there was a nation, before there was a word, there was the need for expression, and this expression came into existence in order to color the colorless loneliness. In Pirosmani, in his art, I have found a lonely artist who understands what life is about — with his art he overcomes and gives color to his colorless lonely life. For Pirosmani, art is liberation and freedom.

I have always wanted to share the solace found in art with the world, with people who feel hopeless and lonely, and to give them hope. I have been curious to see if art would have the same effect on them as I have experienced. That is the purpose of my foundation: to promote the one language that brings us all together — art.

Art is the manifestation of the spirit, and the spirit is infinite. No chains can hold the spirit.

—The exhibition at the Albertina was a success, and even those well familiar with Pirosmani’s art were impressed by the exhibition’s design and by the contemporary artworks which you’ve commissioned as a homage to Pirosmani. Was this your idea? How did you choose the artists? And these artists — Yoshitomo Nara, Kiki Smith, Adrian Ghenie — could you briefly describe the process of collaboration with them? Would it be correct to say that their works enter a dialogue with Pirosmani’s, offer their own perspective on his art?

— It was Pirosmani’s idea, not mine. I only brought it to life. The intention was to fulfill Pirosmani’s desire which he expressed in 1916 to the chairman of the newly founded Georgian Art Society, „…we ought to buy a big table and a big samovar and drink a lot of tea and talk about painting and art. But you don’t want this. You speak of other things.“

I wanted to bring artists through their works around Pirosmani´s Table — to celebrate his 100th anniversary as well as his rebirth in the awareness of hundreds of thousands who had never heard of Pirosmani or seen his art before.

And, speaking of this metaphorical rebirth, the idea was that Pirosmani be reborn surrounded with the living artists who would breathe life into the event.

I was looking for established artists who would be coming from a variety of cultural environments and nationalities and who’d each have found their own artistic language and style.

I was looking for artists who wouldn’t strive in the first place for a superficial, exterior harmony with Pirosmani´s art but bring an inner, organic connection — the free spirit — free language of self-expression, unprejudiced and open mind — I wanted to have diversity and to show that through the language of art we can create a bridge between the past to the present and on to the future, to connect different nations and different styles. The surface is not the essence. I spent hours with the artists and talked about Pirosmani.

Yes, their works enter a dialogue with Pirosmani. Every artist deals with him as a person and with his art. The homage works communicate directly with Pirosmani but remain true to their own artistic voice. Every artist should pay homage to him in their own language. I wanted to show that even accomplished artists from across the world recognize Pirosmani´s art as a source of inspiration.

— Tadao Ando’s Table is remarkable in many ways, as a beautiful work of art object and as an object around which people gather, sit and talk and understand each other. Could you share with us the story of its creation?

—The Pirosmani Table is a work of art with a deep metaphorical meaning. The idea of this artwork originates in the past — in the year 1916, to be precise — and it was expressed by Niko Pirosmani himself.

Pirosmani had remained destitute throughout his life; his works — only partly acknowledged as something more than mere posters — could not save him from poverty. With the full potential of his true talents remaining unrecognized during his lifetime, he was an outcast, even among his friends.

He died a lonely death in 1918 in a basement, and to this day it remains unknown where his body was buried. I have been deeply moved by his tragic fate and his words and promised to myself to create a memorial object for him. A memorial object in the form of a table; a tombstone for him as an artwork paying homage to his love for art. He lived through art and he died being in art. Art was freedom for him, and he died a free person.

The intention was to bring to reality Pirosmani’s idea, his forgotten dream, and in this way to transcend time and space, to connect the past, the present, and the future. To bring together different nationalities and languages, fulfilling Pirosmani’s wish.

So it’s a symbol around which friends can gather to celebrate life, beauty, love, and art; a table that he, Pirosmani, strove to erect during his lifetime.

For his art is above all an art of hospitality: an act of friendship, of welcome, of a shared celebration of simple joys and beauty of life, bringing together the artist and his audience in the same way a hearty and cordial Georgian meal brings together the host and the guests.

His sarcophagus, Pirosmani’s Table, pays homage to the painter’s idea: artists coming from different places have gathered around this table to talk about art. This table can bring together many people — just as Pirosmani wished — including artists, sculptors, architects, poets, educated people, uneducated people, scholars and working people; they will all be able to eat and drink, talk about art, sing, recite poems, and get to know each other, strangers becoming friends. Here is an invitation: come together and celebrate life in its fullest! Make a connection, a bridge that joins the past, the present, and the future — and the only future for humanity lies in unity. This artwork preserves the free spirit — the free language of self-expression and an unprejudiced, open mind.

Art is alive! Art always expresses some form of a mind phenomenon, a particular truth, or a state of mind. It was conceived as a dream of an artist from the past who was poor in life but rich in soul, a dream to build a table — to create a community. This artwork is a body, and the living contemporary artists will breathe life into it!

In 2018, 100 years after his death, the rebirth of Pirosmani’s dream came to reality, and the Table by Tadao Ando was presented in Vienna, the heart of Europe, at the Albertina Museum. To quote Tadao Ando: „As this table will represent the metaphorical tombstone of Niko Pirosmani, I sought to use a symbol which would give a respectful due to his memory, lifetime of work, and Georgian heritage.

The Rose is ephemeral, a fleeting representation of the short space between birth and death. The Rose is graceful, yet its thorns can pierce flesh, so it is a symbol of a contradiction between beauty and mortality.

Why blue roses, you may ask. Blue has a relaxing and soothing effect. It stands for peace, harmony, and fulfillment… With the color blue, we immediately associate the radiant sky and the wide sea. In literature, blue symbolizes the connection between human being and nature as well as our longing for the unattainable.

The color blue also plays an important role in art. The expressionist artists related to the Blaue Reiter group in the early 20th century paved the way for modern art. Pablo Picasso had a stage in his worked called the Blue Period, full of melancholy feelings, and Yves Klein often used in his art only this color.

The table is not a final result; it is a beginning, a symbol of unity and tolerance. All tongues deserve another’s ear and respect; strangers become siblings; there is no difference in value between woman and man, young and old, self-taught and schooled, between the elite and the less privileged… a wandering between worlds..

„There is neither […] slave nor free, there is no male nor female, for you are all one…“ [Galatians 3:28]

—On March 1, Pirosmani exhibition opened in Arles. Congratulations! Niko Pirosmani and Vincent van Gogh — what would you say these two geniuses have in common? It wasn’t by accident that you’ve chosen the Van Gogh Foundation Arles as the second venue for the Pirosmani exhibition. What are the main reasons?

Niko Pirosmani and Vincent van Gogh were born into two completely different cultural and geographical backgrounds. Nevertheless, the art of both painters has certain details that reveal a specific focus on the subject of humanity, which is especially relevant for the present-day art lovers.

Both self-taught artists communicate with the viewer in a very direct way, motivated by a sense of urgency. They create their works in clear connection with „common people,“ turning their artistic eye towards the archaic rural life, the human being who tills the earth in deep harmony with nature and the elements.

Their paintings are glowing images of iconic simplicity and of dreamlike, archetypal life. The style is energetic as the tempo does not permit pedantic lingering on details. The poignancy and forcefulness of the imagery are pushed to the limits. Graphical representation plays an eminent role in both artists’ work. While Pirosmani has a background as a sign painter, van Gogh is influenced by the highly stylized Japanese woodcuts. And most importantly, the Dutch painter is also a collector of those prints, an early form of mass-produced wall decoration made by illustrators who also worked for the newly emerging popular magazines.

Looking at Pirosmani brings into focus his audience as well: who were the people he was painting his pictures for? The popular discussion is dominated by the misleading idea of naive art produced in seclusion, even isolation. This is just as wrong as the assumption that Vincent van Gogh worked without relating to a possible audience. But whereas van Gogh imagined it would come in the near future for him and his „modern friends,“ along with the understanding of new ideas that would mature with time, Pirosmani had been in direct contact with his audience.

— The design of the exhibition in Arles again seems very impressive. How does the exhibition venue — the Van Gogh Foundation Arles — in fluence the concept? What is new in comparison with the exhibition at Albertina?

—At Albertina, we have celebrated Pirosmani’s 100th anniversary and his rebirth in the city of Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele who both died in 1918, like Pirosmani. The focus at Albertina was the idea of Pirosmani’s rebirth in the minds of many who had never heard of him before. The intention was to create a chapel, a shrine, a quiet and peaceful atmosphere. And we have achieved just that. The opening was the most successful in the history of the Albertina Museum, with more than 22,000 viewers following the opening ceremony online. Even our stop-motion exhibition promo clip turned out to be the most successful clip in Albertina´s history with more than 60,000 views, leaving behind even Egon Schiele’s, which reached around 50,000. And the exhibition itself was visited by more than 400,000 people.

To quote the Director of the Albertina Museum, Prof. Dr.Klaus Albrecht Schröder, „For me, the Niko Pirosmani exhibition stands among the most important exhibitions that Albertina has ever done.

In Arles, the place where van Gogh tried to preserve and express the light in his artistic language and where he created one of his greatest masterpieces, our objective was different: to create the opportunity to experience Pirosmani’s paintings in the colors of light. It is in this light, which blesses us with its joy, I intend to show Pirosmani. More specifically, visitors will see Pirosmani on differently colored walls. Pirosmani has never been displayed like that.

And I am very pleased with the exhibition and the curator’s work performed by my dear friend Ms. Bice Curiger, the Artistic Director of the Vincent van Gogh Foundation Arles. I would like to say that this may be the most beautiful Pirosmani exhibition in history. The different background colors of the walls that present Pirosmani’s work in different shades of light is something that has never been seen before.

— What are your plans? What will be the next stop for the exhibition?

—I would like to take the liberty of not revealing that at the moment but I’ll disclose what’s going to be the last stop of Pirosmani’s exhibition journey: The National Museum of Modern Art Tokyo and an encounter with Picasso

—Could you please tell us briefly about the publication´s plans, about the catalogue raisonne you’re preparing with Erast Kuznetsov, art historian and a leading Pirosmani expert…

— As for the catalogue, we are currently in talks with Cahiers D’Art Publishing House, which published the most well-known Pablo Picasso Catalogue Raisonne by Christian Zervos from 1932–1978.